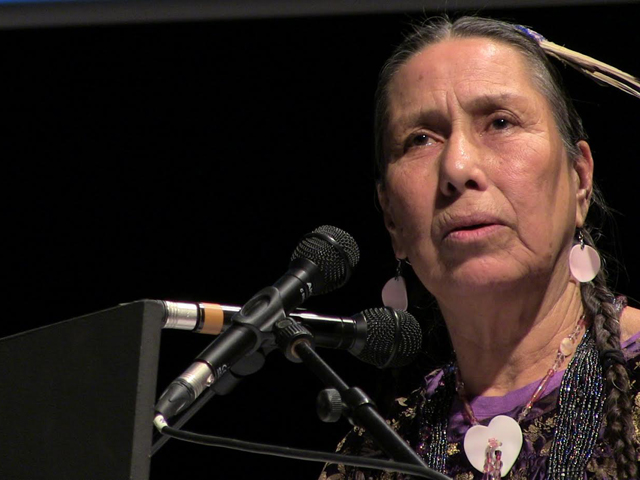

Casey Camp Horinek speaks inside of the United Nations COP21 Climate Negotiations during a WECAN International event (Photo: Emily Arasim/Women’s Earth and Climate Action Network)

Casey Camp-Horinek has a gentle demeanor, with her long, salt and pepper-colored hair and lyrical voice. However, there is searing fire behind her caring, dark eyes.

She was born into the Ponca Nation, a Native American tribe originally from the Nebraska/South Dakota area, and which is now scattered throughout the U.S. Camp-Horinek lives in north central Oklahoma, where approximately 800 reside.

In addition to being a mother, grandmother, and councilwoman of the Ponca Nation, Camp-Horinek – who turns 69 next month – is an activist for all of us.

Camp-Horinek was one of the thousands peacefully protesting at against the Dakota Access Pipeline at Standing Rock, North Dakota, last year. And last month, she came to New York City accompanying other indigenous women leaders from across the U.S., and around the world, for the conference, ‘Indigenous Women Protecting Earth, Rights and Communities’, presented by the Women’s Earth and Climate Action Network (WECAN) to educate the public, as well as CEO’s and shareholders, about renewable energy, earth awareness, and indigenous issues.

“Many of us believe in a seven generation philosophy,” explains the indigenous leader about why she does not give up fighting for justice. “We believe that our people, the past seven generations before, have prayed for us to live in a good way. It is our responsibility in the decisions that we make that we should care for seven generations to come.”

Camp-Horinek hails from a large family. She’s been married 48 years and has four adult children, and over a dozen grandchildren.

“I feel very very fortunate that our family is very integrated in terms of being able to hang out with one another,” she says. “Our grandchildren visit us regularly. We travel, pray, eat and laugh together. Intergenerational life is part of indigenous life. What drives me to activism and environmentalism is a duty of a grandmother, woman, wife, and daughter to carry on the relationships of all living things and caring about what happens to the generations to come.”

Going to Standing Rock, last summer and autumn, was part of that duty.

“It was a horrible, racist, militarized situation,” says Camp-Horinek. “We had more than a thousand arrested, made into less than human feelings.”

On October 27, 2016, she says 141 people, including herself, and her sons, were arrested while praying.

“They wrote numbers with markers on our arms…I’m Standing Rock 138,” says Camp-Horinek, adding that she’s not washing off the ink until she goes to trial in July so she can show the judge. “They put us in these bear cages in a basement…[and] they had militarized tasers, mace and pepper spray in containers the size of fire extinguishers.”

She says growing up on the reservation, she and her people have become used to living with racism, but now she feels they also have to deal with environmental racism.

She describes a Taiwainese business that’s producing carbon, as well as Oklahoma gas lines, fracking, and earthquakes happening as a result of it, as “an environmental genocide” on her people.

“We are one of the cancer capitals of the world – children and elders are dying of cancer,” says Camp-Horinek. “There is a long process that brought us to this. The way the federal government has failed its responsibility to the indigenous people.”

Her grandfather was born in northern Nebraska, where the original Ponca people came from.

“In Oklahoma, there are 39 recognized tribes,” says Camp-Horinek. “The other six are there from forced removal. We had no choice but to leave to ‘Indian territory’ – putting us in one general location – on reservations. My grandfather was eight at the time of the forced removal.”

“In one generation, we had to leave our hunting, growing organic food and fishing,” she continues. “One in three of us died in our Trail of Tears, and we had to depend on the government commodity foods.”

She says being forced to have white flour, white sugar, and dairy – all foods that were foreign to the bodies of her people, caused them to develop all sorts of ailments.

“Now we have the highest diabetic rate on earth,” says Camp-Horinek.

As a councilwoman, she’s one of seven trying to make an economic and cultural way forward for generations to come for her people.

“One of the reasons I’m here today is to stop the expansion of the Keystone XL pipeline,” says Camp-Horinek. “Our kids are 56 percent more likely to develop leukemia, and we already have rampant cancers, and diabetes, and other illnesses. We need to empower our children and great great grandchildren.”

She says she would like them to have basic necessities like clean water to drink.

“In my youth, I could not imagine buying a bottle of water,” she says. “There were natural springs. In our case, there was well water. Now that same well water is completely contaminated from fracking.”

What is one piece of advice you wish you could tell yourself when you were 20 with the wisdom you have now?

“I believe that growth is a healthy, organic, happening, and it has to happen in the manner which your spirit guides you. [You can’t be] constantly looking for the positive growth to take place, that change has to happen in its own way.”