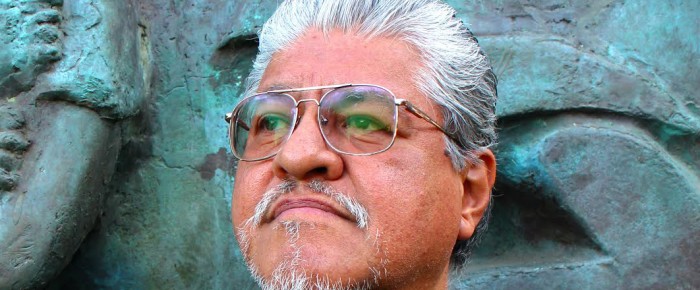

Bobby Gonzalez has had practically every job you could think of — from a medical records clerk in a hospital to customer service at a utility company. However, he says…

Read moreBronx poet uses storytelling to educate others about their history

Bobby Gonzalez has had practically every job you could think of — from a medical records clerk in a hospital to customer service at a utility company. However, he says…

Read more

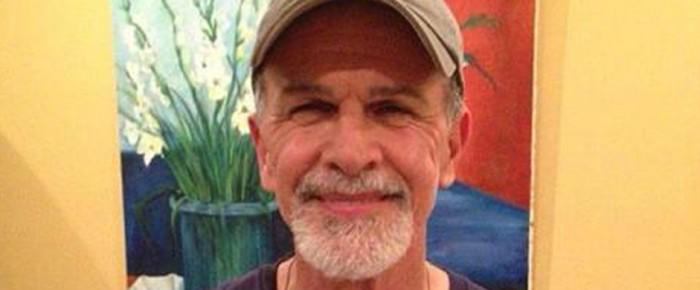

Eugene Ethelbert Miller, who goes by his middle name, “Ethelbert,” is a writer and literary activist who says he’s never been busier than at 66. Originally from the Bronx, NY,…

Read more

Flo Meiler may be 81, but she’s still at the top of her games. She actually competed in 18 different sports last month at the World Masters Athletics Championships in…

Read more

Growing up in poverty in South Central and East Los Angeles, Luis J. Rodriguez says he found himself so emotionally empty that he joined a gang at age 11. He…

Read more

Many might remember Tony Plana from his many acting roles from “Feo” in the film “Born in East L.A.” to playing America Ferrera’s dad in the sitcom “Ugly Betty,” but many might not know…

Read more