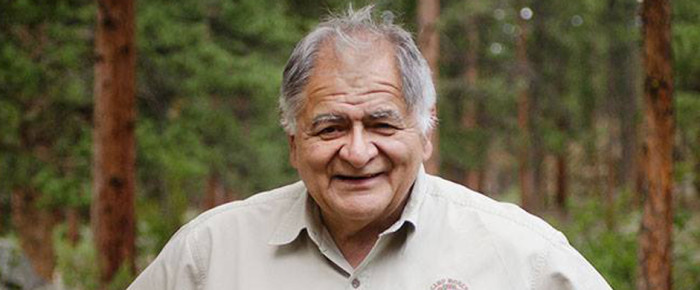

Francisco Stork’s youth was so compelling that it makes for a great novel. He was born in Monterrey, Mexico in 1953 to a single mother from a middle class family in Tampico (a city on…

Read moreFor a former attorney, now young adult author, representation is key