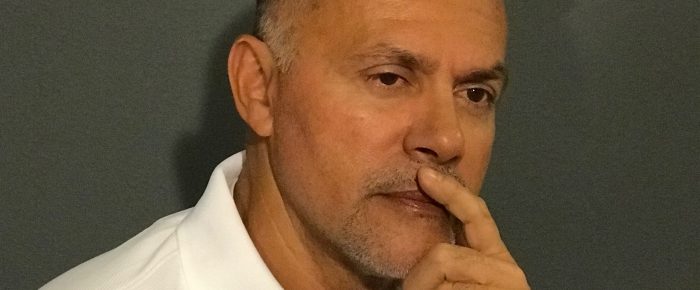

Hector La Fosse has had a life more reckless than most. It all started in New York City, in the 1960’s. La Fosse was born – the youngest of seven…

Read moreFirst-time author describes his journey from addiction and jail to finally freedom

Hector La Fosse has had a life more reckless than most. It all started in New York City, in the 1960’s. La Fosse was born – the youngest of seven…

Read more

In “Playing Catch with Strangers,” an essay published in The New York Times in 2015, Bob Brody writes that he played catch with his father only once in his life. “That summer…

Read more

Maria Aponte was born and raised an only child in East Harlem, otherwise known as “El Barrio,” in New York City, to Puerto Rican parents. Because she lost her mother…

Read more

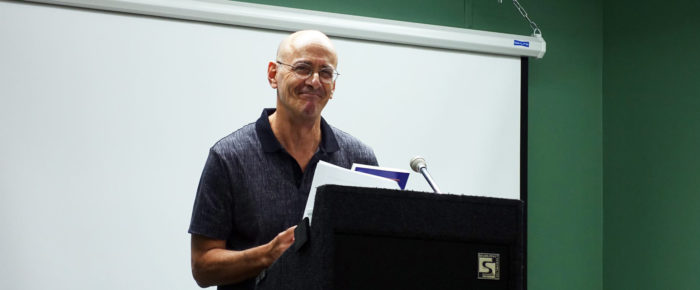

Eugene Ethelbert Miller, who goes by his middle name, “Ethelbert,” is a writer and literary activist who says he’s never been busier than at 66. Originally from the Bronx, NY,…

Read more