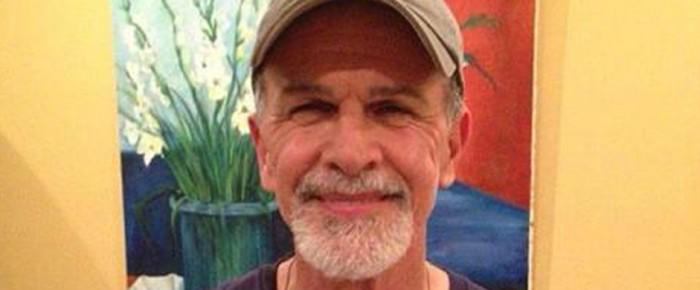

When there’s a problem in San Benito, Texas, Gilbert Galván often comes to the rescue. San Benito is a close-knit city of approximately 25,000, located near the center of the…

Read moreFrom Migrant Farm Worker to Educator, a Principal Unites His Community With Quinceañeras