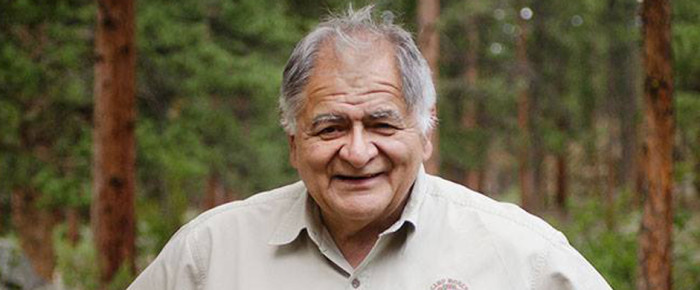

Throughout his life, Roberto Moreno has worn many hats from mountain real estate developer to journalist to mountain hotelier. However at 68, his lifelong mission is not even near completion.…

Read moreA life dedicated to sharing the importance of our national parks