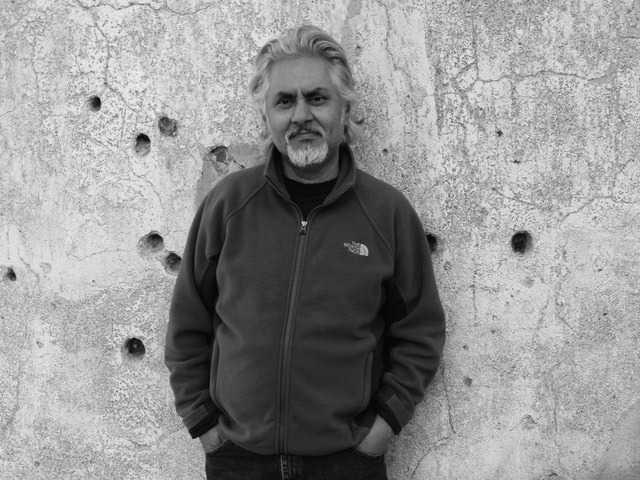

Oscar Hernandez says he isn’t conscious of when he first knew he wanted to be a musician – it just happened. What he does recall, however, is hearing salsa from…

Read moreFrom growing up in the South Bronx to leading the Grammy-winning Spanish Harlem Orchestra