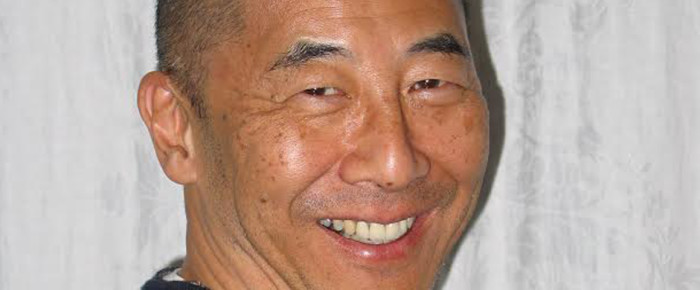

Barbara Aliprantis jokes that she started listening in utero. She was born with a superb memory, an expressive voice, and a vivid imagination – the recipe for the perfect storyteller.…

Read moreA Greek immigrant tells stories to bring people together