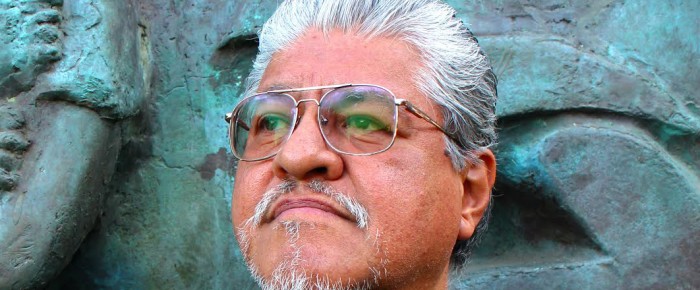

In the Ute Indian Reservation, located in Northeastern Utah, approximately 150 miles east of Salt Lake City, it’s common to hear people say, “I’m going to go see Lacee.” Lacee Harris is…

Read moreNative healer uses traditional ways to heal returning veterans